Pan-Domain Force Employment Concept - A Cyber Review

I look at DND/CAF's Pan-Domain Force Employment Concept from a digital and cyber point of view.

Background: In October 2023, DND/CAF’s Pan-Domain Force Employment Concept (PFEC) received a lot of news coverage, particularly for the foreword by the Chief of the Defence Staff, which describes how Russia and China already view themselves at war with Canada and other Western/NATO countries. The release of this got a lot of attention and led to some frustration by academics and analysts because they could not receive a copy of the PFEC despite it being unclassified. Fortunately for me, multiple sources were kind enough to provide the document and some background information.

Although the PFEC received media attention in October this year, it has existed in some capacity since 2020. As one source described it, it was never released for political reasons. With this information, I decided to check previous ATIPs and found that there used to be a Joint Information Operations Force Employment Concept in 2020/2021. Despite this fact and the previous PFEC existed, I am confident that there have been sufficient edits since this earlier version to keep it up to date.

Foreword

The foreword to the Pan-Domain Force Employment Concept (PFEC) has received considerable news coverage already for General Eyre’s descriptions that Russia and China view themselves as war with Canada and allies, so I will skip over most. The one thing I will note is that the PFEC is described as laying out how to deter, counter, and mitigate the actions of adversaries. As a result, this document should tell us considerably how DND/CAF views its approach to cyberspace and the role of the forces in cyber defense.

To date, the Government of Canada nor DND/CAF have clearly defined the ways and means to which they deploy cyber capabilities. Through access to information process requests with the Government of Canada, I have been able to obtain some information which

Executive Summary

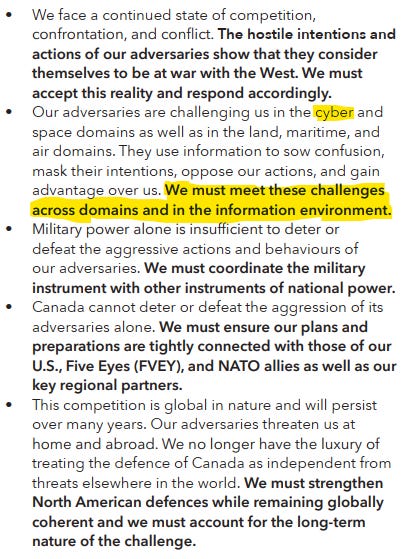

The executive summary lays out how much threats through and in cyberspace are increasingly on the mind of DND/CAF. The executive summary lays out five imperatives. Of the five, one of which directly acknowledges cyber and information, cyber plays a core role in each of the five imperatives.

While a recognition of cyber and space domains is not anything to really make note of, but what is wonderful to see is directly acknowledging the a CAF response is needed in these domains on equal footing as others. While this statement is vague and could mean anything, the optimist in me view it as a potential signal of greater action in these areas. In my recent analysis of the 2022-2023 Departmental Results, it would indicate that the CAF is indeed taken a much much more assertive posture in cyberspace. The CAF has been making fantastic strides over the last year or two in building out its offensive cyber capabilities. It has much to go in terms of integration in joint operations, but there is a need to use these capabilities for the defense of Canada.

Beyond this imperative, we can recognize that cyber is present in each of the others in an indirect way.

Cyberspace is one of the primary domains that hostile states are probing Canada.

Most operations and intelligence in cyberspace is conducted not by DND/CAF, but from the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), other government agencies/allies, and the private sector. DND/CAF is one actor of many. Being a state actor does not make you any different in cyberspace other than having the backing of a state behind you, but this does not automatically translate to strong capabilities.

Canada’s Five Eyes (FVEY) allies and NATO are the primary alliances that Canada will be working through when conducting cyber operations. FVEY is the first and preferred, but since the 2016 NATO Warsaw Summit, NATO has been steadily increasing its cyber capabilities alliance-wide. NATO-led cyber operations will be an eventuality at some point, although not likely anytime soon.

I would describe NORAD modernization as one of the primary motivating factors for DND/CAF digital modernization. While there are many reasons, there is an additional imperative when NORAD is central to domestic defense and maintaining your most valuable partnership with the United States. Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) is one of the central operating concepts for United States NORAD modernization, which is increasingly being referred to as Combined-JADC2 due to the inclusion of allies in this operating picture. As a result, Canada must ensure its protection of cyber and digital assets not just for the protection of Canada, but protection of its allies.

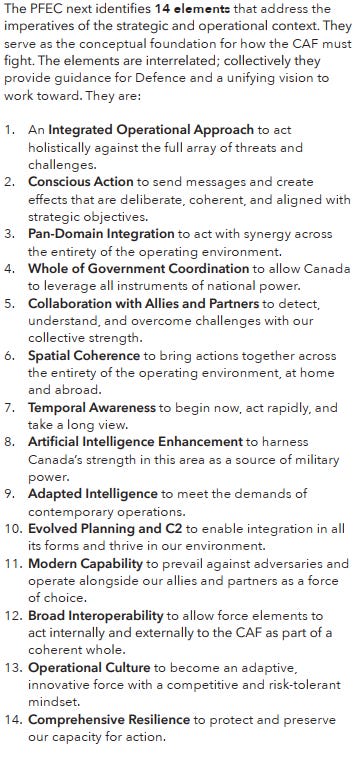

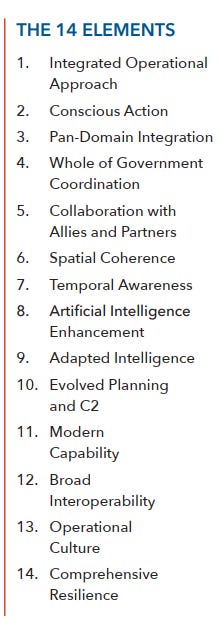

Following these five imperatives, the PFEC establishes 14 elements that DND/CAF are meant to do or take into account in order to address the five imperatives.

My original intent with this analysis was to focus on the key elements which apply to cyber, but these elements are cross-cutting and not meant to be applied to a singular domain or branch. These elements are not core initiatives but direct or indirect guiding principles or traits that the CAF aims to achieve through change. These changes are meant to better prepare Canada to face the challenges and threats that are emerging internationally.

In many ways, we can understand this as a doctrinal shift for the CAF. This can be wrapped up in any language that DND/CAF wishes to, but the core message of the PFEC is that the way the CAF is operating is outdated and must be modernized. This is most evident when its stated purpose is to “describe how Canada’s military power will be used to deter and defend against actors hostile to our national interest.” The context for this modernization is important because, as much as global threats are pointed to, we cannot overlook the deep personnel and recruitment crisis the CAF currently faces. A change to how the CAF operates to maintain relevancy is about its survival as an institution just as much as it is about how the CAF will defend Canada.

Introduction

Foundational to the PFEC is a recognition that the type of conflict that the CAF will be required to face and engage with is not what the CAF has traditionally been trained and deployed to address. The purpose is to stress that Canada’s adversaries seek to harm Canada and its allies through means which cannot be challenged with direct, overt military actions in the traditional domains of land, sea, and air.

Something important to note is the news that the PFEC has existed in some form since 2020 gives this paragraph new meaning. While it certainly should be concerning that DND/CAF continue to withhold information about how it plans to modernize the Armed Forces, the positive aspect from this is that the CAF is actively engaging with how quickly the threat environment is changing. The PFEC of 2020 is different than the PFEC of 2023, and as it should be. If DND/CAF were relying upon PFEC 2020, it would rightly receive criticisms for this in a post-2022 threat environment.

The fundamental takeaway is if the PFEC is a good foundation for modernization, particularly digital modernization? That will be what I will seek to determine in this review today. However, there are second-order purposes that are stated outright in the PFEC as well, which is to serve as a “catalyst for the evolution of the role of Defence within the broader Canadian Government response to emerging and evolving threats.” I find this very interesting for a number of reasons and its implications.

The first implication that springs to mind is the direction of information and response options. What jumps out to me here is that the framing of how DND/CAF will be evolving can be taken in two ways. The first, and I believe the intent, is that DND/CAF needs to change to address the changing character of conflict that requires the Armed Forces to adapt to not only remain relevant as an organization but to be able to support the Government of Canada to face these new threats and conflict. However, one smaller potential read of this is DND/CAF as a catalyst to reinvigorate how defence and national security are treated by the Government of Canada.

This admittedly might be reading a little too much into it, but one reading of this is DND/CAF functioning more as an “advocate” as opposed to an “advisor” on national security and defence issues. Regardless of the party in power at the time, Canada’s military has historically been a victim of its politicization by politicians. One well known and recent example of this is the delay in the procurement of the F-35, but these issues back back centuries and are no exclusive to large capital projects. Despite a history of poor-political attention to Canadian national security and defence, there are many who argue that the inattention to Canada’s national security and defence apparatus has never been worse. Without going too deep into a discussion of this, a potential reading of DND/CAF’s catalyst could be interpreted as seeking to reinvigorate how politicians and Canadians treat national security and defence. A phrase I heard recently, which I think applies to the present situation in Canada, which is that “defence and national security” are not a hobby, and Canada is learning that the hard way.

How they intend to do this is not the flashy capabilities that get the most attention, but is high level strategic and conceptual to how DND/CAF organizes itself. Lucky for me, these issues heavily related to force structures and doctrine, which are my bread and butter.

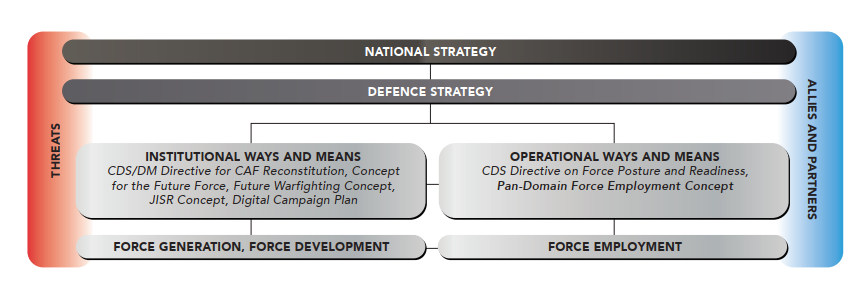

The introduction closes with this graph to situate the PFEC in relation to other strategy documents and how it informs activities in DND/CAF. I quite like this chart as it specifically differentiates between DND/CAF as an institution and structures and how the institution is deployed and operates. This differentiation is something often taken for granted and is why I want to discuss it here.

I am unsure how long it has existed, but there has been a disconnect between the force generation and institutional perspective and the force employment and operations of DND/CAF. A good example of this is the CAF’s Cyber Forces, which have overall lacked an engagement with force employment, and minimal attention to force development. Over the last couple years this has slowly changed, which we can in part likely credit the PFEC and other associated documents listed above. (Although I would be remiss if I did not mention the good work of the new CAF J6/Cyber Force Commander Rear-Admiral Luciano Carosielli, amongst others).

Strategic and Operational Context

This section seeks to elaborate upon what has been referenced thus far, which is adversaries, including Russia and China, are actively seeking to harm or undermine the rules-based international order and Canada and its allies. I could spend all day discussing how this is being done, but important for us is how the CAF will respond accordingly and how it frames these threats.

In short, a significant increase in global state competition and adversarial behavior means Canada must respond and prepare to deter war and work with allies to counter this adversarial behavior. This requires DND/CAF to coordinate with other instruments of national power more closely and ensure coherency and interoperability with allies.

The section closes with saying “We can no longer view the defence of Canada as being largely independent of military developments elsewhere in the world.” This statement would seem to underscore what I alluded to earlier, which is that the CAF may increasingly function as an advocate for itself and speaking more matter of fact. I am unsure how much the thought that Canada was immune to such global development was a problem with DND/CAF, but more so with the Government of Canada. This similar framing and reduced sugar-coating of the issues facing the CAF can be seen reflected in other actions, such as Admiral Angus Topshee’s recent statements about the critical state of the Royal Canadian Navy.

Elements

This section goes into deeper detail about the 14 elements established previously. Rather than review or analyze each of the 14, I will view them as a whole and recommend you to read the PFEC yourself, which can be downloaded at the bottom.

The central encapsulating concept of the PFEC is moving away from siloed approaches to operations. Interwoven throughout each of the elements is the main goal of a CAF that can operate with its various disparate parts more effectively and jointly to face pan-domain threats. As command and control is key to making this happen, this means that cyber and digital capabilities are increasingly important as they are what is the infrastructure to 21st-century command and control.

Pan-domain and cross-service integration relies upon the Army, Navy, Air Force and all adjacent elements being able to communicate. As a result, cyber resiliency will be increasingly important in the future. As an example, let us look at the F-35. One may assume that information and communications technology is tertiary to procuring the F-35. Contrary, it is foundational to most of its advanced technology. The F-35 fighter jet is an air dominance platform, meaning its intent and purpose as a fighter is to have absolutely no potential peer and as the term implies, completely dominate air battles. One way the F-35 does this by having a very advanced suite of electronic devices and capabilities to deny adversaries any advantage they may have. This requires digital and electronic systems on the F-35 to function as they intend and for connectivity between F-35s and joint elements, which support the F-35’s dominance platform.

This also overlooks that this relies upon data infrastructure and capabilities to process the massive amounts of data that the F-35 produces and that simulations are required for a lot of F-35 training due to how much flying an F-35 is an intelligence goldmine for adversaries. Consequently, this means that simulations of the F-35 are simultaneously a national security concern and an adequate cyber defence is needed to protect the F-35 as an air dominance platform. Many 21st-century military advantages rely upon information and communication technologies, as shown, meaning that they are vulnerable to cyberattacks, potentially negating any advantage that Canada or its allies may have.

This is why I stress cyber defence so much in nearly all aspects of Canadian defence and procurement: if ICT and cyber can function as a force multiplier, then they can also serve as a force divider.

Further, an important point related to this is how much the PFEC stresses collaborating with allies. Cyber defence becomes important so that the CAF are not the source of compromise to broader allied military efforts. Working with allies, NORAD and NATO as the chief examples, is central to Canada’s defence and is what makes these alliances so strong. Thus, to be the source of a compromise amongst allies due to an attacker’s lateral movement could have major diplomatic and defence concerns. The United States is increasingly adopting an approach of combined joint all-domain command and control (C-JADC2), with the “combined” referring to the combined networks of allies.

Suffice to say, cyber defence becomes important for Canadian defence and maintaining our diplomatic and security relationships with our allies.

Campaigning

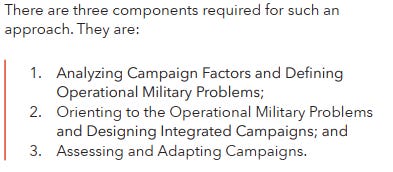

This section is dedicated to a discussion of how the CAF is shifting to an approach of “campaigning” to focus on the CAF’s “most acute operational military problems.” While I was already aware of this shift to campaigns, this is the first time I have seen a discussion of how the CAF views its use. Contextualizing campaigning as the mechanism to address the CAF’s most acute problems would be in line with my reading of the CAF Digital Campaign Plan, which is meant to help the CAF try to catch up.

In a very reductive sense, this is about systemic problem-solving and the CAF has many systemic problems. This also begins to better understand and explain the format of the CAF Digital Campaign Plan and its staged planning and steps in digital modernization.

I am very happy to see how they are framing factor intervening variables, particularly in putting cyber and information on par with physical. This is an important distinction to make as cyber and information have traditionally been viewed as subordinate or tertiary issues, but are now receiving due attention.

Conclusion

The key takeaway from the PFEC is the above. Broadly speaking, the PFEC situates the CAF to modernize for pan-domain operations, but chiefly about situating the CAF to be problem solvers. As the great Dr. Andrea Charron once jokingly put it: Stop being so good with so little. When Dr. Charron said this, it was 2020. The key point of this statement is not that the CAF needs to start doing bad, but accepting the longstanding issues the CAF faces in terms of normal operations and existential are not tenable.

The CAF must change because it has no choice. These issues are very much about maintaining Canada’s defence commitments, but also existential to the existence of the CAF as a functional and effective force.

Takeaways

Digital modernization is about capabilities as much as it is about personnel.

Firms and leaders must view digital modernization in terms of its impact on labour and workflow. Software and capabilities which reduce administrative burdens and time mean greater time to spend on force readiness.

The Government of Canada and the Minister of Defence have signalled that no major new money is coming to Defence. While there may be fluctuations in terms of where money is going and how it is allocated, DND/CAF needs to be much more judicial with how it is spending. As a result, costs are likely to be viewed a lot more critically. A recent comment by ADM Materiel Troy Crosby alluded to recognizing when increased costs are not justified.

De-centralized bespoke approaches will remain the norm until ~2025. Digital Campaign Plan establishes that from 2025 and onwards, the Digital Transformation Office and other information and communications components of the CAF will have a greater role in centralizing digital modernization

This means the contacts you have or departments/groups you sell to will be changing in the next few years. Especially with digital and cyber products, a lot of solicitation occurs outside the normal procurement processes. Procurement rules are a lot looser for the purchase of services or goods under $25,000 and, in many cases, do not have to require a public posting. As the centralization of digital modernization takes hold, this is likely to change and alter existing practices.

Although the procurement rules will not change, authorities and processes are changing in DND/CAF. As a result, firms must be proactive about how they fit into these plans and ensure their business capture processes adapt accordingly.

You can download and read the Pan-Domain Force Employment Concept here.